Lost but not forgotten architecture

I am proud to unveil the first four multi-media pieces in my new collection, “Lost American Architecture: In Memoriam.”

As the name suggests, they are depictions of stunningly beautiful buildings that came down long before their time. In each case their fate was sealed by a simple act of unprovoked aggression. They each fell to the ground in a cloud of dust, victims of the deadly wrecking ball. Today they are long forgotten memories, like weathered tombstone inscriptions in a graveyard of architectural destruction that spans a century and more.

While nothing can bring these elegant art forms back to life, I created these paintings to honor their intricate craftsmanship and pay tribute to the men and women who designed and built them and those who lived or worked in them and most importantly, those who tried to prevent their demise.

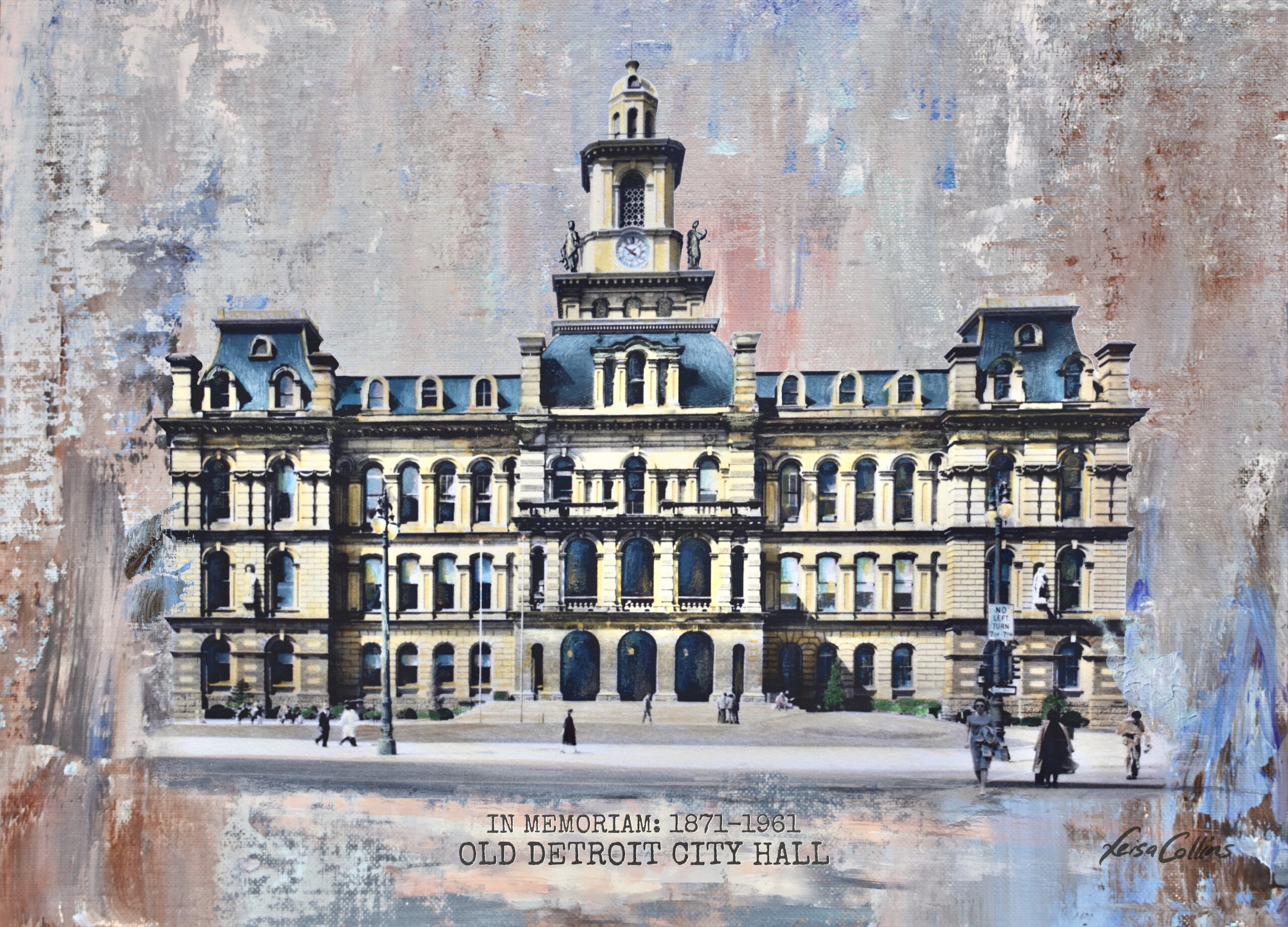

DETROIT OLD CITY HALL: IN MEMORIAM 1871 – 1961

It’s hard to fathom that this beautifully crafted Italian Renaissance Revival masterpiece that took ten years to construct, is now lost forever. Built to last in Amherst sandstone, the Detroit City Hall, in the state of Michigan, was the center of life in Detroit for almost 100 years.

In 1861, plans for the building were completed by architect James Anderson and the old City Hall of Detroit, Michigan, opened in 1871. The three-story building had an observation deck and a large clock tower. Situated in downtown Detroit, the City Hall served as the seat of government for the city of Detroit, Michigan from 1871–1961. Almost every year since its opening, its booming bell summoned hundreds of couples to City Hall on new Year’s Eve, where they would kiss at the stroke of midnight.

The interior of the building also had beautiful features, such as black walnut and oak furnishings and the floors were covered in black and white marble. Natural light poured into the courtrooms and offices through 15 large windows on each floor.

Despite a poll showing that Detroiters favored preservation of the building, in January 1961 the Common Council of Detroit voted five to four to demolish the building. Preservationists took the fight to stop the demolition all the way up to the United States Supreme Court, but sadly all requests for injunctions were denied.

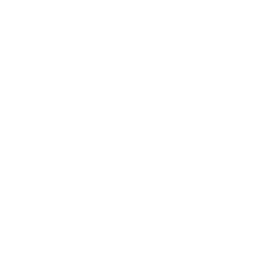

CHICAGO FEDERAL BUILDING: IN MEMORIAM 1905 – 1965

The Beaux-Arts Chicago Federal Building opened with great fanfare in 1905 and stood for 60 years in the heart of downtown Chicago. Designed by Henry Ives Cobb, the six-story building was renowned for its majestic rotunda which was capped by a done more than 100 feet in diameter, larger than that of the Capitol in Washington. Inspired by the architecture of Rome, it’s featured polished granite, white and Siena marble, mosaics and gilded bronze. At the center of his creation Cobb placed a trompe-l’oeil oculus or eye where white clouds perpetually drifted across a blue sky.

The Chicago Federal Building housed federal courts, the main post office, and other government bureaus. In fact Walt Disney, who was born in Chicago, worked at the building in the post office around 1918. And in 1931, the courtroom of Judge James Herbert Wilkerson was the location for the trial and sentencing of gangster Al Capone.

By 1960, the building was said to be too small for government use. Despite the valiant efforts of preservationists, it was demolished in 1965 and replaced by Mies van der Rohe’s modernist Kluczynski Federal Building—a far cry from the historic grace of this lost treasure.

The Chicago Federal Building is considered to be one of the city’s greatest architectural losses, and sadly, its destruction added another Beaux-Arts masterpiece to the growing list of demolished structures in the city of Chicago.

OLD PENN STATION NEW YORK CITY: IN MEMORIAM 1910 – 1963

When Pennsylvania Station opened in 1910, it was considered a traveler’s respite and was a far cry from labyrinth of underground tunnels that occupies the space today. An impressive gateway to New York City, the station covered eight acres in midtown Manhattan. The building was inspired by the Roman Baths of Caracalla and it had a magnificent coffered ceiling that rose 148 foot. One entered onto light-filled train platforms beneath a canopy of iron and glass. It was designed by renowned New York architectural firm McKim, Mead & White and was considered to be one of their finest masterpieces.

The New York Times proclaimed that “it was the largest building in the world ever built at one time.” when the station officially opened on August 29, 1910. Their article included a projection of how the population of New York City area would balloon to 8 million by 1920—and that transportation infrastructure would need to keep up.

Hard times struck in the Depression, and by the mid-1950s, the Pennsylvania Railroad has become a victim of cars, planes and general urban decline. In early 1960, the Pennsylvania Railroad announced their plans to tear down the station to build Madison Square Garden and the dungeon-like Penn Station we know today. In response, leading architects and artists of New York picketed in front of the original Pennsylvania Station, trying to save the monumental art form.

In October 1963, demolition crews began hacking away at the limestone walls, stone eagles, and thirty-foot tall Doric columns of old New York Penn Station. The demolition and rebuilding of the new station took five years.

With the passing of the old Penn Station, it was realized that no mechanism existed for the public to object to the destruction of historic architectural landmarks. As a result, activists pressured the city government to pass New York’s first ever landmarks preservation law in 1965.

The demolition of the monumental old Penn Station is positioned by architects as a defining point within the historical preservation movement in this country, as stated by leading New York City historian Kenneth Jackson: “Human beings, myself included, have an unfortunate tendency to appreciate people and things only after they are gone. Pennsylvania Station is the catalyst for the historic preservation movement.”

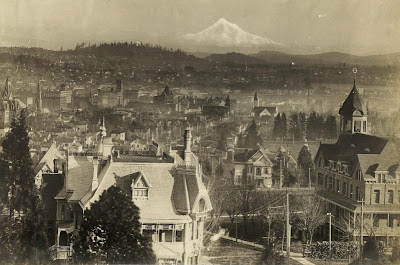

C.M. FORBES HOUSE PORTLAND: IN MEMORIAM 1889 – 1929

This fantastically ornate Queen Anne home, on the northwest corner of SW Vista Avenue and Park Place in Portland was completed in 1889 for Charles M. Forbes, a partner in a successful furniture store who also served on the Portland City Council.

Relatively little is known about the history of the home, however it was considered to be a showpiece for Mr. Forbes. Its location on a hill overlooking Portland, served as a noticeable “billboard” for its owner, advertising the type of work produced by his furniture factory and store. The house appeared on postcards that tourists and travelers could buy at downtown Portland pharmacies and stores. A few months after Mr. Forbes untimely death his home was offered for rent, all rooms completely furnished, including a pool room with a fine billiard table.

The house was demolished in 1929 and eventually replaced with an apartment building.

Later this month I will be offering a canvas print of one of these paintings as a giveaway, so stay tuned! In the meantime, please do all you can to spread the message that we need to protect our historic architectural gems.

Until next time,

Leisa